GRAPHIC DESIGN Samantha Cass

The two-day Financial Times Luxury Summit (Nov. 23-24) was, like all events this year, entirely virtual. Designers, CEOs, developers, economists, professors, and more converged from around the globe to discuss everything from “Winning Over Gen Z” and“Diversity and Inclusion” to “The Future of London’s Property Market.” High profile speakers included Alexa Chung, Sandra Choi, and William P. Lauder (CEO of Estée Lauder Companies). The two most interesting, and perhaps radical, takes on the future of luxury come down to digital fashion and sustainability.

In other words, catering to Generation Z.

As a fashion student, luxury is something I study, not something I participate in. When thinking about the luxury industry, I am presented with an ethical conundrum. Much about the luxury fashion industry is unattainable both financially and stylistically. The garments and accessories are prohibitively expensive, the events are inaccessible, and the lack of diversity is demoralizing. Luxury fashion is damaging to the environment and many of the old fashion houses are hesitant to stray too far from their traditional styling and cater to younger consumers. At the same time, we are conditioned to desire luxury, to covet what we cannot have. We see our favourite celebrities and influencers wearing nothing but designer and we’re told through social media that we need to strive to be like them in order to be beautiful, happy, and successful.

Despite the unprecedented challenges these circumstances have presented, many brands and retailers have been able to swim instead of sink.

What’s most intriguing about this year’s summit is the way 2020—as described by FT Fashion Editor Lauren Indivik—has been a “reactionary year.” Every stop on the fashion chain from production, to distribution, to consumption was touched by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the unprecedented challenges these circumstances have presented, many brands and retailers have been able to swim instead of sink. Experts in the field like Gary Wassner, CEO of Hilldun Corporation, are optimistic about the luxury industry because “the luxury consumer never went away.” While there wasn’t necessarily a unified agreement as to whether the future of luxury is going to be strong, there is a general consensus that the pandemic didn’t cause struggling business or closures, but rather accelerated those that were already in progress.

The Digital Frontier

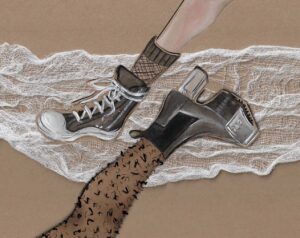

One new avenue of fashion that is unexpected, and definitely foreign to the traditional industry, is the virtual fashion frontier. Last year, in what Riot Games called the “first-ever collaboration between a global eSport and a luxury fashion house,” League of Legends partnered with Louis Vuitton to create in-game designer skins and an LV capsule collection inspired by the game. This wasn’t LV’s first foray into the gaming world; in 2018, they collaborated with FIFA World Cup. The cross-pollination of consumers in both luxury fashion and eSport gaming might be unprecedented, but it’s certainly an innovative way to get a new market engaged in luxury fashion.

While the link between clothing and gaming is new, it isn’t an altogether shocking development. Digital fashion that is defining ‘cutting edge’ is the work that people like Kerry Murphy of Fabricant are doing. Murphy’s aim is opposite to the LV and League of Legends collaboration; instead of blending the physical and digital together, he wants to separate them. The gist of Fabricant’s work seems to be to create and sell digital clothing that never gets made and translate the interactive experience of shopping into the digital space. As their website states, they “waste nothing but data and exploit nothing but our imagination.”

Sustainability

The promise of sustainability is an alluring one, especially for younger generations. Brands across the industry are trying to convince their consumers that they are sustainable when in reality, many of them are just greenwashing. Maxine Bédat, Founder of New Standard Institute, works to reframe our thinking of sustainability in the fashion industry: “If the industry’s busy working on incremental changes while the cultural conversation doesn’t shift, we’re not going to actually achieve what needs to be achieved.”

Alex Weller, Marketing Director of Patagonia Europe, spoke about the relationship between brands and consumers in moving to a more sustainable future: “Once it’s out there in the world, there is a level of shared responsibility between Patagonia and our customer community to look after that thing for as long as we can. And when it has reached the end of its natural life to find the best way to bring it to [the] end of life through recycling and upcycling.”

Recycled, reused, upcycled, and secondhand all seem to fall under the term ‘second-life.’ While Patagonia is taking steps to promote the second-life model in their ‘Worn Wear’ campaign to reduce the carbon footprint of their production and their consumers, they also recognize that second-life clothing is attractive to their younger customers, whose passion for sustainability and need for lower price points often prevents them from participating in designer or luxury fashion.

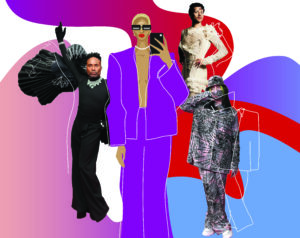

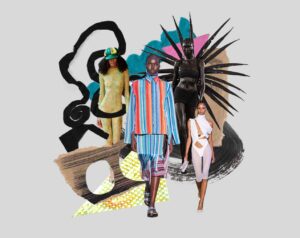

Catering to Gen Z

In his talk, aptly titled ‘Winning Over Gen Z,’ Olivier Rousteing (Creative Director of Balmain) discusses the ways he has brought an old fashion house like Balmain into a younger generation. For Rousteing, in this new era of fashion, “the meaning of luxury has changed. Luxury before was really about being exclusive… Today, luxury feels more authentic.” In his time at Balmain, Rousteing has taken pains to introduce simpler products like t-shirts and sneakers to engage younger consumers and to make parts of Balmain more accessible to a wider audience.

At the time of his appointment to Creative Director, Rousteing caused “grumbling” with his youth, relative anonymity, and his race. His fresh perspective livened a house that was out of touch with young millennials and Gen Z. He prides himself on diverse casting, styling, and partnerships, and upholding the history, design, and craftsmanship of Balmain while also making it more democratic, international, and inclusive. Rousteing, who “would rather be hated for who [he is] than loved for who [he is not],” states that “the brands that are luxury [are those] who [have] strong messages to help the world to change. This is a real luxury.”

The Need for Shared Responsibility and Accountability

While there was a degree of optimism rippling throughout the summit about the future of fashion and the future of luxury, there is also a notable shift in the perspectives included. There’s a lot of judgement aimed at consumers participating in a fashion system in ways that isn’t always wholly sustainable or perfectly ethical. Consumers do have a responsibility and the power to ‘vote’ for brands that align with their values, but for many on the lower-income and lower price point side of the industry, this isn’t always possible.

The industry, especially luxury brands who like to think of themselves as imaginative and innovative, as noted in the ‘Diversity and Inclusion’ panel with Kimberly Jenkins of Ryerson University and Lindsay Peoples Wagner of Teen Vogue, need to be held accountable on all fronts. If these brands really are as innovative and visionary as they say, bringing their business models, hiring decisions, and sustainability practices shouldn’t be such an unattainable feat. On the shifting narrative of responsibility, Bédat succinctly summarizes this need:

“There was this assumption before that we’re just fulfilling consumer demand, without a recognition that the industry was spending a lot of marketing dollars generating that demand to begin with…There is the beginning of a recognition now of the role industry plays in creating the demand for which it then fills.”

Disclaimer: The author is a personal assistant to Prof. Kimberly Jenkins of Ryerson University. All of the author’s opinions are her own.