GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Patricia Gascon

WRITER: Rachel Ecker

The practice of tattooing and the embodiment of fashion is grounded in self-expression and the visual communication of identity. Yet, there is a pervasive legacy of disconnect between these two worlds.

Kae Palmer-Leclerc, a tattoo artist for Ink & Water Tattoo, discusses the works of Ed Hardy, an early 2000s tattoo artist that sparked tsunamic sartorial trends by bringing American traditional tattoo motifs to mainstream fashion. “You would see people like Nicole Richie, Paris Hilton, and Lindsay Lohan wearing Ed Hardy. But you would never catch one of those girls dead in an American traditional tattoo shop,” says Palmer-Leclerc. Palmer-Leclerc explains that the tragic perk of this tattoo-inspired fashion is that those who do not want to fully delve into the tattooing world “can just toss those clothes out and go onto the next identity. Whereas for some people, this is our identity.”

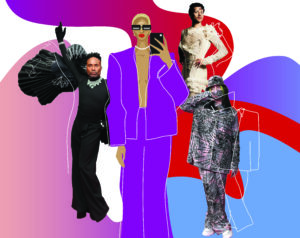

More contemporarily, the luxury fashion house Viktor and Rolf’s Spring 2020 show featured an array of models in overtly frilly dresses with sizable collars and bows; silhouettes that can be associated with delicateness and innocent femininity. The models were also covered in large-script temporary tattoos. The vision of the show was “tough but innocent.” A narrow representation of tattoos was used to communicate connotations of criminality in contrast to the softness of the garments.

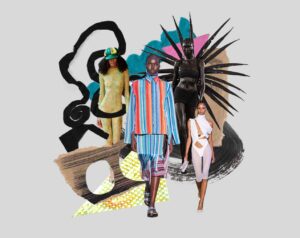

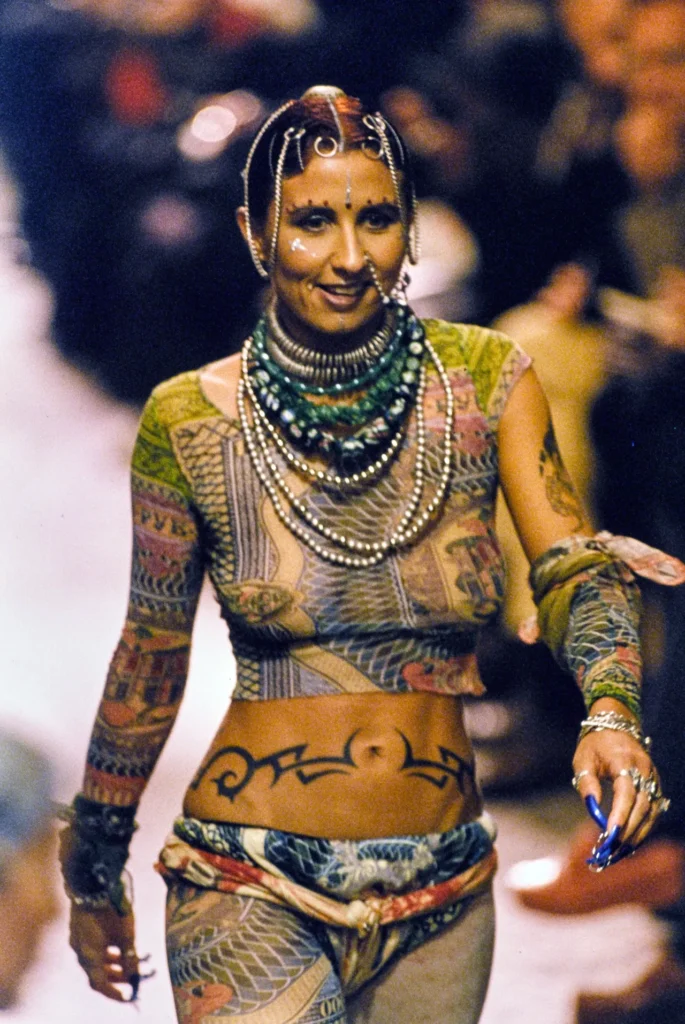

The fashion industry perceivably projects irreverence towards tattoos, positioning them as caricatures of their unruly and rebellious connotation. However, there are key players in the fashion world who have represented tattoos from a celebratory position. In 1994, Jean Paul Gaultier created a collection called “Les Tatouges,” which saw models wearing their real tattoos, piercings and long nails as dominant accessories on the runway. Rebecca Arnold, Lecturer in History of Dress and Textiles at The Courtauld Institute of Art in London, suggests “Gaultier’s models were not simply blank canvases in which he could showcase his designs, but real people with the agency to alter their bodies who lived outside of the world of Gaultier.”

Ketzia Sherman, a tattoo artist and Contract Lecturer at Humber College and OCAD University, discloses that tattooing in North America originated as “an Indigenous practice… and it was a very queer and female based practice.” Sherman explains that as a symptom of colonization, “it was very much something that was erased with much of Indigenous culture.” The Europeans that migrated to Canada brought with them a rich history of tattooing practice, and as the work of erasure was imposed, the two styles started to meld. Into wartime around the 1940s and 50s, tattoo marketing saw a dramatic shift towards a male-dominated audience with the imagery of the Marlboro Man, correlating white masculinity with the painful process of tattooing, and further excluding women, Indigenous people and people of colour from that community.

Today, the widespread use of social media has created a platform to deconstruct this outdated notion. “There’s a lot more, very public Indigenous practitioners who are bringing original practices or doing modern interpretations,” says Sherman. Amanda Routtenberg, a third-year student at X University in the Creative Industries program, represents a voice of Generation Z as she shares, “Tattooing doesn’t seem as big of a deal to us. I think social media has a lot to do with that because one person who you admire or who is an influencer, let’s say they get a tattoo. As a few people get [tattoos], then it’s like an outbreak.” TikTok and other major social media platforms have highlighted the commonness of tattoos, effectively erasing its taboo spectacularity for younger generations.

[…] Tattooing in North America originated as “an Indigenous practice… and it was a very queer and female based practice.”

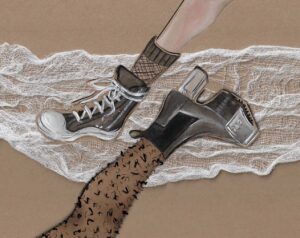

Despite the murkiness between fashion and tattooing, tattoos are still widely considered to be a form of fashion. Ketzia Sherman illuminates Joanne Entwistle‘s theory of The Fashioned Body: “The thesis is that the fashioned body is a socialized body. So to dress and maintain your physical appearance means that you are a part of a social structure. Tattooing is very much a part of that. It is a way to enter a culture or a subculture to say, I am a part of this group.” Gabby Cleveland, a fourth-year journalism student at X University, connects the inherent link between fashion and tattoos to expressions of identity. She explains, “My cowboy hat, for example, is something that represents who I am, a culture that I like, where I live and what kind of music I listen to. Then my palm tree tattoo represents my childhood and growing up in San Diego. They both represent times of my life or things that mean a lot to me, but are completely different.”

The source of disconnection between these two expressive worlds stems from a key incompatibility: the permanence of tattoos and the disposability of fashion. Sherman diligently defines, “Your tattoos are permanent to you, but they’re temporal in space. That tattoo dies with you, that tattoo ages with you and decays with you. That’s one of those things that clothing doesn’t, you never get to see that because most of our clothing will just never go back into the Earth.” Perhaps it is the demand of defining categories in our capitalistic society that fuels this complicated comparison between fashion and tattoos. Perhaps it is the job of acceptance to simply acknowledge these two worlds as distinctly their own but that nonetheless are powerful communicators of identity.

“Your tattoos are permanent to you, but they’re temporal in space. That tattoo dies with you, that tattoo ages with you and decays with you. That’s one of those things that clothing doesn’t, you never get to see that because most of our clothing will just never go back into the Earth.”