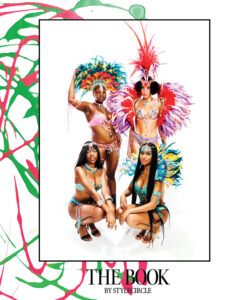

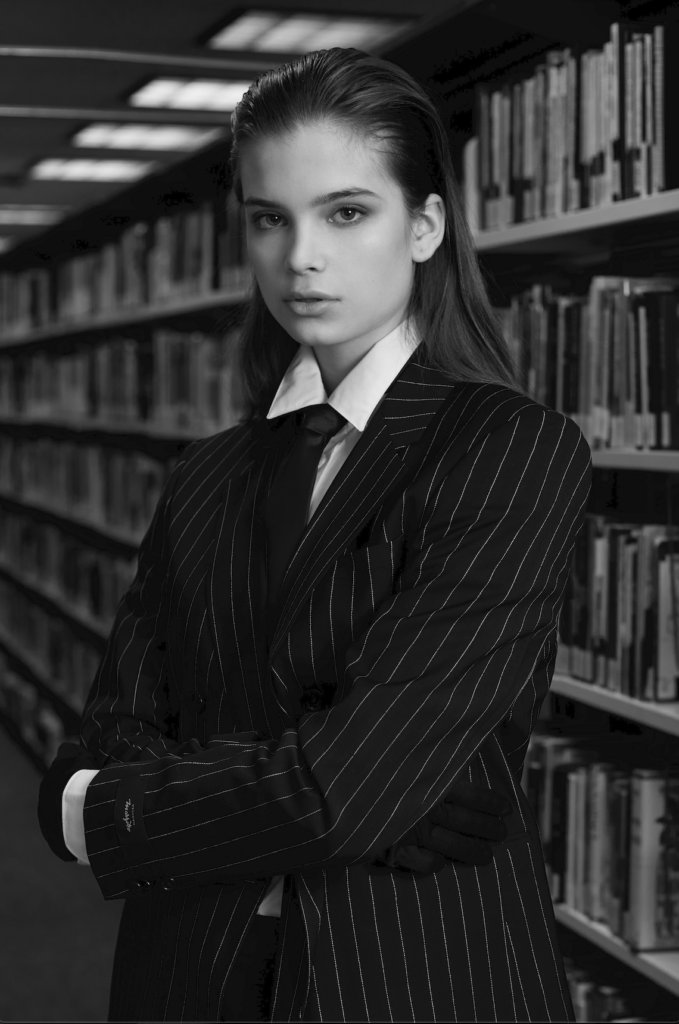

PHOTOGRAPHY Freya De Tonnancour

WORDS Noah Holder

STYLIST Mia Vos, Steve Nguyen

MODELS Alice, Brandon, Isaiah (Elite)

VIDEOGRAPHY John Delante

Commonly the suit is understood as inherently masculine. Through a historical lens, the documentation of male suiting existed for two decades before the recording of feminine bodies in the early inklings of the uniform. Often worn by men of power, (ie. Military men, men of the King’s court and generally affluent folk) the intention of suiting demarcated men of assigned privilege and importance.

The history of the suit is extensive, and the uniform, despite undergoing countless variations, is still considered a staple in contemporary wardrobes. As most things rooted in the traditions of ancient society, the suit is entrenched in the gender binaries and hierarchies that modern society is continually jockeying with. The suit acts as a battleground over the years for gendered struggle and representation. How does the history of the suit lend itself to further deconstruction of contemporary thought, and dismantling the innately skewed perceptions of power and the body?

George ‘Beau’ Brummell is understood to be the godfather of modern suiting, elevating the simple white tunics that Charles II asked the men of his court to wear, and transformed the idea into the 3-piece suits folks are still familiar with. Brummell was designing exclusively for masculine spaces, specifically, army men and surgeons, his suits were tightly fitted. They created intense ‘V’ shaped silhouettes, referencing ancient Greek sculptures as most arts of the neoclassical period sought to do. It was when the fin-de-siècle came to a close in the early 1900’s, that Brummell’s blueprint was solidified creating the suiting zeitgeist that exists today. Subsequently, the understanding of suits and the power they hold transformed with the lengths of the collars, widths of a tie and the bodies who sported them.

The end of the 19th Century saw the illumination of feminist thought in suffragette movements, and thus suffragette suiting. Women who sought to protest the marginal reality of their society not only took to the streets but to their closets. Suffragette suiting was a ‘man’s’ three-piece suit adorned by a woman who would most likely be smoking and bike riding all around town; subverting norms through dress operated as a multi-faceted tool. Women were demanding socio-political power and assumed the symbol of power through clothes, commandeering traditionally masculine uniform women protested, gained physical freedom (opting for trousers as opposed to large sweeping skirts), and started to widen the scope of fashion.

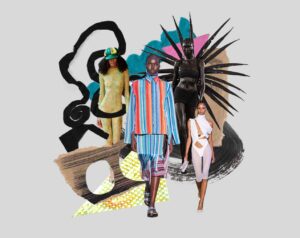

The European women of the early 1900s were not the only folk to kick up clothing hierarchies. In the 1940’s African-American folk sported Zoot suits, which were obnoxiously over-sized often with pocket chains swinging from the blazer pocket down to their knees. Amidst the great depression, folks were aggravated by the suits’ over-use of materials that should be saved or could have been used in the war effort. Pachucas, Mexican-American women often associated with Mexican gang culture, wore Zoot suits, alongside Pachucos, as a symbol of no-nonsense mindset.

The understanding of suits and the power they hold transformed with the lengths of the collars.

When the world, battered and bruised, started to turn again, urbanization was in full effect, and the suit became the uniform of the workplace. By the 1960s, 40% of women had joined the workforce, and in 1966 Yves Saint Laurent gave the world ‘Le Smoking Tuxedo.’ Saint Laurent’s effort was a dramatic shift back to feminine suiting, off the heels of the 50s; a decade that saw the rise of Christian Dior, the designer whose first collection introduced ‘The New Look.’ The slim skirt demanding a nearly impossible waist was a return to the silhouette that The New Women of the 1890s had attempted to terminate. Dior’s outbreak collection of 1946 saw models in slim two piece skirt and blazer that’s waist almost disappeared when turned sideways, it sat a little higher shortening the torso and elongating the legs, replaced the 1890s sweeping skirts that prevented women from riding bikes, and the new midi skirt landed just above the ankles.

Famously, Bianca Perel Mora Macias wore a white ‘Le Smoking’ suit on her wedding day; yet Saint Laurent’s tuxedo still saw women refused service at certain bars and hotels. In these instances of seizing and revisioning suitings traditions, marginalized folk found a new power, consciously appropriating a symbol of power to invoke their own.

Power dressing had come into full effect in the 70s and 80s and is continually redefined. Women’s blazers held padding in their shoulders and loosened the fit; blazers grew bigger, which attempted to take up space for marginalized bodies in the workplace. Critics of the early 00s often thought women adventuring into suiting had gone too far. In constantly chasing power in the form of a masculine ideal, there left little room for power to be truly redefined. As suiting had not yet been deconstructed and stripped away from the constraints of gender binaries, folks worried women were sacrificing too much. They were simply striving for the masculine ideal of power instead of seeking ways towards equity. As the turn of the decade approached masculine suiting had a rough patch in all aspects. Blazers kept growing in size, and so did the trousers. Don’t believe me? Google any year from the 90s and add ‘NBA Draft Class.’

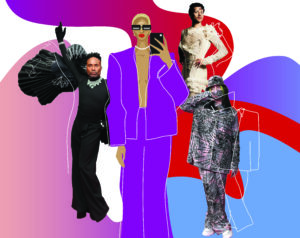

As the year 2000 rang in, suiting had lost a vest and become a two-piece affair, blazers tightened while trousers grew and vice versa. The uniform evolved had been met with countless revolutions, and yet the inherent masculinity of the garment had been no more or less deconstructed than years prior. The masculine suit saw few changes unlike that of women’s suiting. Despite going to and fro with lapel and knot size, and jockeying with the severity of the ‘V’ shape from the neck to the first button, Masc suiting saw no revolutionary change. Contemporary designers such as Peter Do have begun to tackle suiting, returning to the ethos of three-piece suiting yet in the result of a bolero jacket covering the blazer, or better yet asymmetrical skirts styled overtop trousers giving the wearer the option of all or nothing. Bianca Saunders FW2020 saw the revisioning of a suit vest by elongating its form and calling to the coattails of conductors. Despite both collections having to be categorized by deciding in which week, Men’s or Womenswear, the designers aren’t seeking to fit a specific body, moreso attempting to push the aesthetic conversation of suiting forward. As a result, Designers such as Peter Do may be making Womenswear, yet their clothes are not bound to the weeks they release a new collection.

The suit is entrenched in the gender binaries and hierarchies that modern society is continually jockeying with.

Although queer bodies have graced the earth since people became, well, themselves, their presence has been historically suppressed and demands often quelled. Although the bout over suiting had acted as a game of tug of war with men and women jockeying for position—and men seldom moving an inch—suiting had yet to be unhinged from the binary it’s founded upon to understand what androgynous bodies desired from the uniform. The suit is often still perceived as a masculine manner of presenting, while women use suiting to illuminate themselves and take up arms. Similar to how the Pachucas used Zoot suits as armour, most attempts sought to attain a cis white male ideal of power. Brands like WILDFANG or Bindle & Keep, all seek to create clothing, especially suits that prioritize garments that create confidence and comfort in one’s own body instead of striving to imbue bodies with masculine form and presence.

As the new decade does nothing but further the deconstructive tone of the year we’ve left behind, suiting continues to exist as a symbolic battleground. When masc, and feminine bodies fall into the same workplace, the need to mold oneself in the image of power managed to, in a sense, solidify power as masculine through form and shape. Yet as bodies reach to wear whatever makes them feel powerful, in the office and beyond it, the suit can’t be done away with. Rather, the uniform must be taken up and pulled apart. The issue is not that suiting brings power and confidence, it is more so who we believe is allowed to wear them, and how we perceive othered bodies in the uniform.