GRAPHIC DESIGN Brennan March

Lehja. It is an Urdu word that refers to the demeanor one adopts in their speech. You can have a soft lehja, a tough lehja; you can even have a sinister or carefree lehja. Regardless of what your personal lehja is, your word choice is a strong factor in determining it; language is important.

We know in English you have synonyms: large can be big but it can also be massive or gargantuan. Each word’s meaning differs ever so slightly, yet the core of their definition remains the same. The exact word you choose to convey your ideas can shape and alter entire worldviews, especially when you are a corporation in a position of power.

Recently, Fair & Lovely, a popular skin-whitening cream in South Asia, announced that they were renaming their product and dropping “fair” from the title. Hindustan Unilever Chairman and Managing Director Sanjiv Mehta announced the product’s name change to Glow & Lovely, claiming: “We are making our skin care portfolio more inclusive and want to lead the celebration of a more diverse portrayal of beauty”.

How can you possibly do that when the premise of your entire product is built on division and colourism?

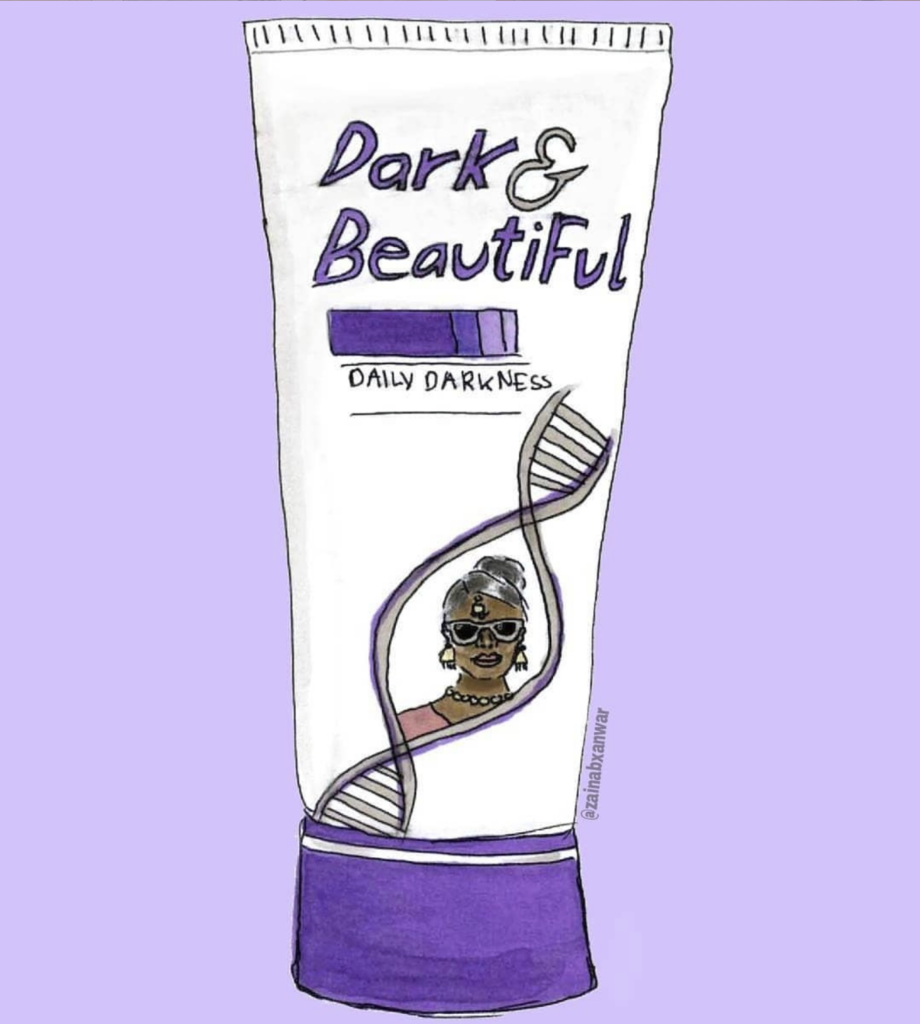

Fair & Lovely is quite literally the subject of countless South Asian artworks aimed at tackling the effects of colourism on mental health.

To say Unilever is unaware of how detrimental their Fair & Lovely products are to their users is laughable. Fair & Lovely is quite literally the subject of countless South Asian artworks aimed at tackling the effects of colourism on mental health.

The discussion of skin whitening creams’ negative effects on mental health is a constant, ongoing one. These brands have had countless advertisements featuring prominent Bollywood stars, like Priyanka Chopra advertising Pond’s White Beauty, with elaborate storylines insinuating that lighter skin means more beautiful and desirable. The market is lucrative, and the message is clear: white skin will lead to better material conditions, love, and happiness.

The question here becomes one of marketing or production: what actually matters? We can debate either way, that the marketing affects young minds; that even if the products weren’t marketed, there would be those out there seeking them.

What is concerning is Unilever’s decision being influenced by the optics of the situation. In light of the global Black Lives Matter protests, the action this corporation thought would be significant was to change their skin-whitening product’s name; they essentially thought that repackaging whiteness would serve as a substantial action. Call a spade a spade. As though changing the word “fair” to “glow” does anything for the suffering of those who are victim to colourism.

It is an active acknowledgement that there is serious, harmful colourism and anti-Black rhetoric that plays out in violent ways, an acknowledgement that the product can feed these ideologies. This incredibly superficial action is brought on with an elaborate statement, as if to imply that Unilever is gracing us; doing us a favour, and we should be thankful to them.

On the topic of colourism in South Asia, I think there is an additional, often overlooked point to make here as well. While we are all well-aware of the effects of colourism within our own communities, we overlook the effect these values of “white is best” have when we leave our homelands. In Diaspora, when such beliefs are imported, they have the potential to lend themselves to some nasty anti-Black rhetoric.

It is one thing to be aware of the larger dilemma of undoing the psychological trauma colonialism left in the Subcontinent, but it is quite another thing to profit off that lasting trauma.

Even with acknowledgements that the desirability for whiter skin stems from the lasting effects of colonialism and caste systems in the Indian Subcontinent, rather than solely the marketing of these products, the ethical question of whether these products should exist remains unanswered. That acknowledgement simply exposes that it is a conscious decision on Unilever’s part. It is one thing to be aware of the larger dilemma of undoing the psychological trauma colonialism left in the Subcontinent, but it is quite another thing to profit off that lasting trauma.

Moreover, such profiteering does not actually take concrete steps towards undoing the trauma. After all, if your livelihood depends on others feeling that they are inadequate in some way, why would you want these people to suddenly feel completely satisfied in the way that they are? Ultimately, it’s about the bottom line.

How does it go? “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the……”