GRAPHIC DESIGN Samantha Cass

When I visited my neighboring town’s shopping mall the other day, the atmosphere was quite unsettling. The long, empty corridors appeared to me as stills taken from Chantel Akerman’s ‘News From Home’; my eyes became a camera anxious for any life form to step into frame. But all I could sense was the overwhelming presence of nobody and a sound that I could now recognize as an air conditioner at work. After my many years of retail experience, I had concluded that there is nothing that could separate people from their shopping sprees. However, something neither I nor stores like Gap Inc. and Macy’s could have anticipated was the threat of viral infection disrupting capitalism’s workflow. The deeper into the mall my friends and I went, the more the sound of the air conditioner fell out of my focus. Instead, as we passed fast fashion stores, a voice in my mind would loudly call out an appalling headline I had previously read about each of them. Before I can open my mouth to say “Let’s go to H&M!”, the voice calls out, “H&M lays-off 1200 garment workers in India without warning, endangering the livelihoods of many”. Victoria’s Secret leaps out at us from around the corner, shouting “We Don’t Use Prison Labor for 0.80$ an hour!….anymore!”.

When the fashion industry is examined, it is the maintenance of White supremacy that unifies the many brands, models, and clothing materials we love.

It is no coincidence that all these fashion stores have the exploitation of People of Colour in common, both in the production and selling of garments (According to the research institute Demos, 17 percent of Black and 13 percent of Latino retail workers are living below the poverty line); nor is it a coincidence that these businesses are largely run by White people (i.e. Helena Helmersson, CEO of H&M, John Donahoe, CEO of Nike, Jay. L. Schottenstein, CEO of American Eagle Outfitters). When the fashion industry is examined, it is the maintenance of White supremacy that unifies the many brands, models, and clothing materials we love. As the underrepresented voices of minority communities grow louder, it has become clear that to buy into the dreamy narrative capitalism has created for fashion is to be complicit in participating in a system built on oppression and the glorification of Eurocentricity.

Fashion’s centering of Western society undermines the contributions racialized communities have made to creative fields, leaving them ignored or blatantly appropriated by White creatives…

In order to be better allies to People of Colour and members of the fashion community, here’s a short guide on how to cut a few of the puppet strings from which Western-European standards of fashion dangle consumers.

1. Un-Idolize/De-Colonize

Participating in fashion is advertised to the public as a portal into a dream life of excess, demonstrated through cross country photoshoots aiming to capture the excitement of living in a big city. I can’t count on one hand the number of times I’ve walked into malls in northern Ontario to see stores brandishing shirts covered with graphic monuments to New York City and Los Angeles. When you combine those images with the heavily promoted ones of Vogue US, Anna Wintour, events like the Met Gala and iconized moments in history like ‘The Swinging Sixties’, French New Wave and Woodstock, everything in the media seems to point to Western-European society as the beacon of all things style. There’s no shame in enjoying cultural movements or great pieces of European art; its hard not to when the media is saturated with the images of white people. It’s necessary to recognize that the reality of centering America or Europe as fashion gods is dehumanizing to all those who do not fit into the racial makeup. A study by Hesse-Bieber and Nagy in 2004 found the dominance of Eurocentric media can have negative effects on consumer’s mental health, especially for people of color as it instills colorism and eating disorders in many communities. Fashion’s centering of Western society undermines the contributions racialized communities have made to creative fields, leaving them ignored or blatantly appropriated by White creatives (infamous examples being the retitling of bantu knots, a historically Black hairstyle, as ‘twisted mini buns’ in a now deleted post by Mane Addicts and Julien d’Ys styling models in cornrow wigs for Comme Des Garcons’ Fall/Winter 2020 menswear show).

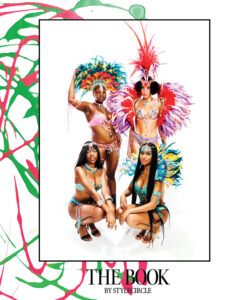

To be better industry participants, we must make our knowledge of style boundless; actively seek out racialized creatives, and amplify the oppressed aspects of their history. Invest in local indigenous film festivals; according to the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian’s Native Networks initiative there are 32 of them across North America alone. In the age of COVID-19 movie lovers can still look forward to imagineNATIVE’S Online Film + Media Arts Festival that features over 100 indigenous artists“to celebrate[s] Indigenous storytelling in film, video, audio, digital and interactive art. From May 28th to the 31st, Indigenous Fashion Week will be held at the Harbourfront Centre, featuring captivating works from Indigenous fashion designers and artists like Victoria’s Arctic Fashion and Amy Malbeuf. A few of my favorite resources for keeping up to date with all things fashion and non-Eurocentric are: Nichelle Gainer’s blog (and best-selling book), “Vintage Black Glamour”, and the writings of: Bri Malandro, Rashida Renee, and Wanna Thompson, three Black women whose fashion journalism celebrates historically Black aesthetics and amplifies the voices of Black creatives. Toronto excited to schedule a viewing at one of the city’s most fascinating art spaces, BAND Gallery, this summer. The gallery, which displays a variety of work from visual art to photojournalism, is “dedicated to supporting, documenting and showcasing the artistic and cultural contributions of Black artists and cultural workers in Canada and internationally”.

2. Support/Organize Locally

A Eurocentric narrative encourages fashion industry participants to maintain an exclusivity centered around the world’s 1% and the “fashion capitals” they rule over, such as London, Paris, and Milan. When consumers break away from that narrative, we will be able to recognize that our local fashion retailers are the ones who can benefit the most from our financial support. No, this is not to mean your local Old Navy, but, instead, emerging creatives of Colour. Allyship can be revolutionary as supporting these creatives helps to disrupt the status quos of nepotism and cultural appropriation committed by brands. Amazing resources for doing so can be found at Black Owned Toronto: a promotional page run by Kerin John for Black-run businesses in Toronto, and Buy From A Black Woman: a non-profit organization that builds a directory of Black female business owners. The Government of Canada has an Indigenous Business Directory that lets you search for Indigenous owned businesses by province, product type or market interest.

The Eurocentric dream that capitalists create distracts consumers from having conversations about racial injustice with communities who really need it: their own surrounding neighbourhoods. I became aware of how important it is to organize locally during the marches organized by Black Lives Matter Toronto in support of Justice for George Floyd and Regis Korchinski-Paquet. Although Toronto is a hot-bed for police brutality against Black lives (Korchinski-Paquet died during a wellness check where six Toronto police officers were present), the solidarity march that was organized in my hometown of Aurora, Ontario brought out thousands of protestors demanding to be heard. When we ignore the racism growing right at our doorstep and let it quietly build, we actively communicate that the voices amplified by Eurocentric standards of success (i.e. celebrity and wealth) are the only ones worth listening to. Put your ear to your community: believe in its ability to produce compelling fashion and in its potential to combat casual racism.

3. Eco Consciousness Is Key

At one end of the fashion industry, we have fast fashion giants like Zara producing approximately 840 million garments every year, which is alarming when you consider “the amounts of annual textiles waste that goes to a landfill in the UK and the US are estimated to be 350,000 tonnes and 9.5 million tonnes” (M.A. Bukhari, et. al, 2018). The designer end of the spectrum is equally as appalling, with Burberry burning $37 million worth of stock, adding to our planet’s mounting waste issue.

One of the important aspects of that issue to remember is that most of the textile waste gets exported to landfills in “East Asian or African countries” (V. Jacometti, 2019), causing disproportionately “higher levels of exposure to toxins and subsequently higher levels of illnesses among minority communities” (P. Newell, 2005). When consumers use their dollars to support these brands and adopt their attitude of recklessly disposing garments, we help to normalize and continue the dominance of European colonialism by encouraging economic and medical disparities between White people and People of Colour.

The shopping-wearing-disposing experience can be personal in theory, but the way consumers spend unequivocally affects the environment we live in, some way or another. On the surface, you may be throwing away a five year top from Forever 21, but that action expresses the privilege we have in North America of not having to clean our own messes. Eco-conscious clothing is the new wave and the need to embrace it is urgent. To stay up to date on how to be more sustainable, websites like Good for You and Ethical Brand Directory offer lists of brands to know and support.

4. Find Out Who Made What

In addition to being exposed to toxic textile waste, it is often garment workers across Asian and African countries who are making the clothes the Western world consumes. Zara garment workers are estimated to earn approximately $500 per month, which is significantly lower than the industry standard pay (N. Tokatli, 2008). This exploitation of racial minority workers cannot continue to be the norm; it shouldn’t be normal that every other week, another rich White billionaire is in a scandal for exploiting their employees. Many brands don’t make their accountability statements public, making it difficult for consumers to get full transparency. In this instance, shopping with local creatives or secondhand is a consumer’s best option at avoiding contributing to the financial oppression of garment workers. It’s encouraged to reach out to brands and advocate for transparency and answers towards how they plan to be allies instead of turning away from the poverty and deaths their labour costs employees. Garment workers aren’t the only ones mistreated by White-owned corporations and white industry CEO’s; it’s important to know the faces and names of these fashion giants as they perpetuate various forms of abuse at every level. For example, retailers like L Brands (owner of Victoria’s Secret, Pink, previously La Senza and Express) and owner Leslie Wexner were in business with the MC2 modelling agency as recently as 2018; an agency which was run by Jean-Luc Brunel who has been accused of multiple accounts of sex trafficking in connection with Jeffrey Epstein. Epstein victim Virgina Giuffre claims that he, Brunel, and MC2 associates “deliberately engaged in a pattern of racketeering that involved luring minor children through MC2, mostly girls under the age of 17, to engage in sexual play for money”. The price of consumers’ vanity is the mental and physical abuse of children across the world. Transparent alternatives to these fashion giants can be found at ethical resource pages like the Ethical Fashion Guide and the Ethical Fashion Initiative.

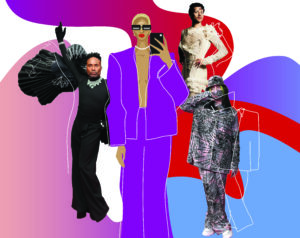

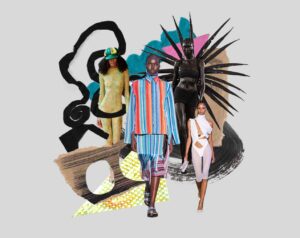

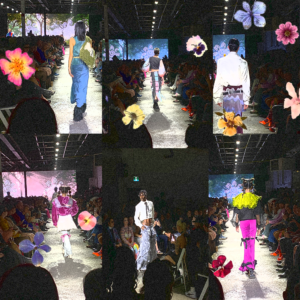

Considering transparency is very difficult to find in the fashion industry, consumers should be taking their time to gather information about their shopping decisions. As Zara and fast fashion giants announce their next sustainability plan, I encourage consumers to only grow more suspicious. Accountability doesn’t end with performative statements: it is the duty of consumers to continue to pressure these brands until the mental, financial, and environmental oppression they perpetuate upon racialized minorities is no more. If North Americans want to see the end of systemically racist violence, it is important that we inspect the ways White supremacy is upheld in all institutions and media in our lives. Fashion doesn’t need to be a tool to advance European ideals; Black-owned brands like Telfar, Phlemuns, and Pyer Moss’ expressions of style show the world that fashion only benefits from celebrating racialized, sustainable creatives. The vision that they bring to the table is extraordinarily valuable and needs to be amplified by all of us who want a future where People of Colour have to suffer for the clothes we buy.