GRAPHIC DESIGN Brennan March

Like any popular social media platform, TikTok has fostered a unique culture of its own. Users create and interact with content in a way that’s specific to the app, and even further, specific to whatever “side” of TikTok their algorithm may have filtered them onto.

Depending on how frequently you use it, you likely have videos on your “For You” page that seem like they really were made for you. A person’s “For You” page can offer interesting insight into an individual’s personality and interests. Largely populated by Gen-Z users, the trending formats can also offer insight into parts of popular culture. One example of this is a trend started by Tatianna Ringsby (@tringsby) that she refers to as “being feminine the way boys are.”

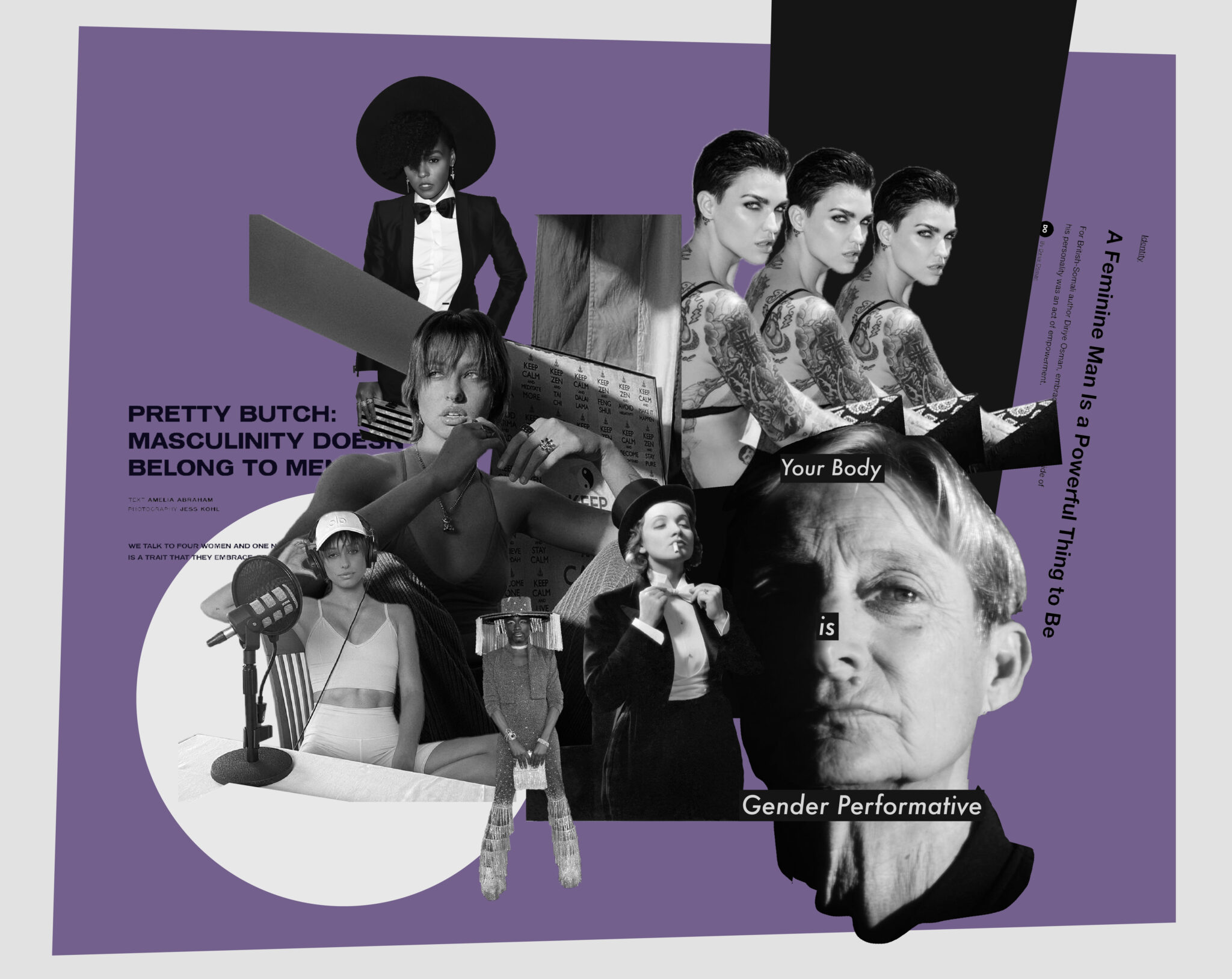

Gender and sexuality are huge topics on TikTok, and although the kind of content seen is largely dependent on the users, the impact of content that engages with gender and sexuality is undeniable. VICE wrote about Femboys in August 2020 and i-D wrote about MaidTok (a trend that featured men and masc folks dressing in sexy maid costumes, often with their girlfriends by their sides) in December 2020. The New York Times published an article in October entitled “Everyone is Gay on TikTok.”

For insight into what the e-boy look is, I recommend this Dazed article from July 2019 as a starting point. I would be remiss not to note here that the majority of these articles are focused on men and masc folks exploring their gender and sexuality, with less mention of women and femmes.

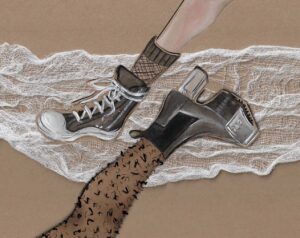

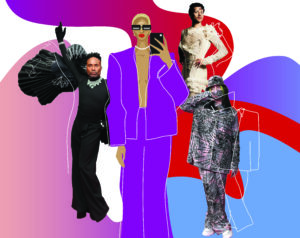

Now, the concept of “being feminine the way boys are” will make sense to some, and be extremely confusing to others. Ringsby, a genderfluid and queer femme-identifying creator, employs fashion, makeup, and hairstyling trends that resemble the e-boy look that is popular among Gen-Z boys and masc folks. This includes masculine silhouettes, smudged eyeliner, silver chain necklaces, and heavy contour.

The transformation process is set to a trending TikTok sound, and is usually around 15 seconds long. As of Feb. 22, 2021, Ringsby has posted at least seven videos of the same concept, with one of those videos reaching 9.2 million views and nearly 2 million likes. The original sound has been used in over 1000 other videos and has been recreated countless times by other users on the app, including by well-known queer creators like Marth W (@marthwubbles).

It would be easy to see these videos as another trend focused on aesthetics, but the notion of being a femme person accessing feminity through a masculine lens offers an interesting perspective on gender. As a cis queer woman, a fashion scholar with a background in sociology, and a frequent user and creator on TikTok (both personally and professionally), my interests intersect in a unique way that informs my understanding of this trend and its broader meaning.

What is most personally compelling about these videos is how they make me reflect on the way my queerness does or doesn’t interact with my gender presentation.

At first, I thought the concept was a product of the patriarchy, the feminine was being processed through the masculine in order to make it acceptable. Needless to say, that first impression didn’t last long.

In careful consideration of the trend’s implications, and in recognition of the creator’s queer identity, I read up on Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity. Butler’s work as a gender theorist is instrumental to our current understanding of gender as distinctly different from biological sex. It’s key to note that gender “performance” and “performativity” are different and that Butler believes that “nobody really is a gender from the start.” She says that our behaviour, speech pattern, dress style, and more produce gender as a phenomenon about us rather than something that comes from within us. Butler, while acknowledging this idea is perhaps controversial, says that gender is the way we give an “impression of being a man or a woman.”

Ringsby, who also creates lifestyle content on YouTube, Instagram, and co-hosts a podcast, has evolved over the last several months in creating content about her identity, sexuality, and queerness in addition to other aspects of her life. She uses she/they pronouns and says she does everything in “a queer way.”

So while I was initially held up on what the implication of accessing femininity through the lens of masculinity might be, I have since focused more on what it means for gender identity and gender fluidity as a whole. What is most personally compelling about these videos is how they make me reflect on the way my queerness does or doesn’t interact with my gender presentation.

“Being feminine the way boys are” is a broad statement, but in the context of TikTok is pretty concretely understood as embodying a feminized masculinity. Perhaps it’s not femininity that’s being processed through masculinity, but the other way around.

Regardless, I view this trend as a disruption of the gender binary, and one that demonstrates that the feminine and masculine exist simultaneously and interconnectedly, even if one is being more embodied than the other in a given moment by a given body. While the videos are fun, and an excuse to dress up and do a cool makeup look and hairstyle, they also provide a space for women and femme folks to explore their gender in a unique way.

For queer women and femmes, TikTok is a relatively safe space to explore and engage with their queerness and connect with their community. This trend is just one of many ways that queer folks have established community on TikTok, and the increased normalization of gender diversity in mainstream culture.