GRAPHIC DESIGN Brennan March

Using the dance floor as a space to analyze the abuse of political power is a feat one can only expect from the transportive and boundless imagination of disco.

To me the most powerful thing about disco is its ability to invoke a fantasy. As a kid I’d run upstairs to my parents’ room where their stereo and CD’s were kept, flip through the CD case, and slide the Boney M ‘Greatest Hits’ record from its sleeve. My heart would race as the frantic, rhythmic clapping intro of Rasputin poured through the speaker; my lips spreading into a smile as I sneakily turned the volume dial from zero to 10. By the time the ‘Rah-Rah-Rasputin’ section comes on, I would be lost inside the irresistibly groovy imagery that singers Frank Farian, Liz Mitchell and Marcia Barrett created of snowy early 20th century Russia. Using the dance floor as a space to analyze the abuse of political power is a feat one can only expect from the transportive and boundless imagination of disco.

I’d alternate between this and the soundtrack to the 1998 film ‘54’, a CD stocked with two discs of songs that make your heart ache and head unconsciously nod along to the beat until your shoulders and hips join in. I’d jab the broken ‘NEXT’ button with a pen to jump to The S.O.S. Band’s ‘Take Your Time (Do It Right)’, an extremely passionate plea to work through an argument with a lover. Mary Davis’ powerhouse voice effortlessly managed to make my eight-year-old self feel the heightened intensity of romance, despite not having experienced anything romantic up to that point.

Today, the power of disco persists despite the popular claim that it is dead. One consistent aspect of disco, whether during its peak in the 1970’s, or its revival in pop music throughout the 2000’s and 2010’s, is the celebration of Black, LGBTQIA+ culture, and feminism. These everlasting communities are central to what keeps disco in the public eye; it’s the genre’s history of loving all people from all backgrounds that keeps it in business. I’ve put together a walk down disco’s diamond studded memory lane, highlighting the many moments that put disadvantaged minorities first.

A Vehicle for Women’s Sexual Liberation

One of my favourite Donna Summer songs is ‘She Works Hard for the Money’, a ‘four on the floor’ disco anthem celebrating and empowering working-class women. Summer’s discography demonstrates her belief in the multifaceted nature of women, highlighting their ability to be both hard workers and masters of their own sexual prowess (one example being ‘Bad Girls’, a fiery track about sex workers getting money from male customers). Disco was an era of music and fashion that amplified the roar of the sexual revolution. One of my favorite artists, Jane Birkin, spent the latter half of the ‘60s and ‘70s representing female sexuality in her music, most famously on her duet with Serge Gainsbourg, ‘Je t’aime…moi non plus’ from 1969 and ‘Lolita Go Home’ from 1975. Mid song on the former track, Birkin walks us through a breathy, moaning orgasm (which made the track the first #1 record to be banned in the UK) and on the latter song laments about bar patrons who call her ‘une pute’ for the shortness of her socks and skirt. Through the combination of eroticized vocals, Gainsbourg’s funky production, and her style of low hanging jeans and see-through sequin dresses; Birkin subverted male fantasies of womanhood by deciding for herself how she’d be perceived in the public eye.

In addition to inspiring women to advocate for their sexual freedom, disco also gave room for sex workers to find success in music. One significant moment in disco history would be the release of Andrea True Connection’s ‘More, More, More’ in 1976. With the release of the sex-positive track part-time pornographic actress Andrea True found herself becoming a disco star overnight.

Modern history shows us that female liberation continues to persist and fight against the obstacles of patriarchal society, and as a result, disco has only continued to champion their voices. Black female entertainers like Beyoncé have made use of the genre and style in expressing her sexuality on songs like ‘Blow’ for her notoriously feminist fifth studio album ‘BEYONCE’. The line: ‘can you eat my skittles? It’s the sweetest in the middle’ feels most at home in the equally sweet and inviting soundscape of Pharrell’s groovy production. Many chart topping hits of the last few years use disco in a similar way, such as Katy Perry’s ‘Birthday’ and Doja Cat’s ‘Say So’.

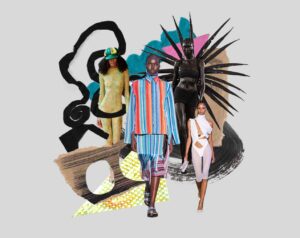

Reclaiming Positivity- Specifically in Black Communities

It’s no coincidence that many of the disco songs that carry themes of liberation, relaxation and triumph have Black entertainers behind their production. When Maurice White sweetly sings Earth Wind and Fire’s ‘September’, there is something bittersweet about the way he reminisces for a time when there ‘never was a cloudy day’. The lyrics to 1970’s hits like Kool and the Gang’s ‘Celebration’, CHIC’s ‘Good Times’ and Gloria Gaynor’s ‘I Will Survive’ reflect the resiliency of the Black community; specifically in relation to the racist violence experienced throughout the Civil Rights Era. Disco became the soundtrack of many Black-only clubs around North America, offering a unique perspective of Blackness apart from colonial Western-European values.

As civil rights protests experienced a slow down of direct action in the late 1970’s, Black musicians worked to use their lyrics as vehicles for uplifting their community. Researcher Kesha M. Morant describes these actions as “funk musicians recogniz[ing] language as a form of social control, thus ending their blind consent to manipulation through language by developing a counterdiscourse that challenged accepted social norms” . Not only did these musicians express their love of Blackness through song but through African specific aesthetics that became popularized during the disco era. Afros or long, beaded braids for the hair, dashikis and flood pants for the outfit; often Maurice White would be wearing at least one of these fashions when performing. For White, this was a way of connecting to his African/Egyptian ancestry and sharing the value he has for Black history with audiences across the world.

A film example of the celebration of Blackness through disco can be seen in The Wiz, the 1978 Wizard of Oz remake starring Diana Ross as Dorothy. The film features an almost entirely Black cast and a soundtrack by Black musicians; a work that demonstrates the importance of supporting each other in the black community. These values are still apparent in today’s disco media, such as Blood Orange’s third studio album ‘Freetown Sound’, 17 songs that amplify stories specific to Black identity with the help of Black musicians like Kelsey Lu, Ian Isaiah and Zuri Marley; daughter of one of the most prominent figures in Black music history. When I’m in a modern disco mood but it’s time to celebrate, I’ll switch gears to Snoop Dogg’s ‘Bush’ from 2015, a record that uses the genre to create a sound as energetic as any Nile Rodgers output from the 1970’s.

LGBTQIA+ Revolution

A favorite off of the 54 soundtrack would be Thelma Houston’s ‘Don’t Leave Me This Way’, a song that began as an international hit and became an anthem for LGBTQIA+ people faced with the AIDS epidemic. In a 2013 interview with Xtra, Houston asserted that “to have my song associated with that movement, especially in terms of making people more knowledgeable, particularly about the AIDS crisis, I’m proud.”. Disco created a safe space for LGBTQIA+ people to exist without the fear of being ostracized; in the 1970’s and 1980’s the dance floor catered to all of American society’s misfits.

Clubs like Candy Factory, GG’s Barnum Room, Paradise Garage, The Loft, and Ice Palace 57 were famous for their queer-inclusive dance floors. The notorious Studio 54 provided a stage for queer icons like Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop to build their influence; conflating their counterculture artistry with the free-wheeling attitude of the discotheques. During this period, Warhol and collaborator Paul Morrisey made some of their most politically active work that cites inspiration from the characteristics of the disco era. Namely Women in Revolt starring transgender actresses Jackie Curtis, Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling as newly sexually liberated women who form P.I.G. (Politically Involved Girls) to fight back against systemic sexism and homophobia/transphobia.

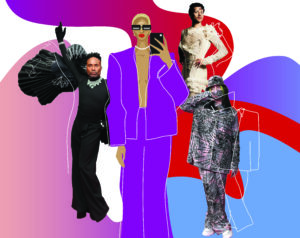

Disco also provided an avenue into the music industry for many queer artists, one of the most famous being Divine, the iconic drag performer who lead many of John Waters’ most celebrated films. Divine’s commitment to counterculture in film was immediately transferrable to the inclusive world of disco music and gave the world ‘I’m So Beautiful’; an anthem against bigotry and rejoicing in one’s own differences. The aesthetics of the genre helped to queer our understanding of masculinity and femininity through the introduction of falsetto-voiced singers like Barry, Maurice and Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees. Disco inspired Grace Jones to sport a more androgynous look, which offered the gender bending cover art for her fifth studio album ‘Nightclubbing’. While appearing flat-chested and broad shouldered, Jones would sing songs penned by men, like her career-defining track ‘Demolition Man’ that was written by Police frontman Sting. When Jones presents herself to the listener as a “walking nightmare, an arsenal of doom’ who ‘kills conversation as I walk into the room’, it becomes clear that she is not here to embrace traditional notions of femininity but would rather embody stereotypical male gender roles; the provider, the closer, the aggressor. The queer inclusiveness of disco continues today, though most popularly embraced by outspoken icons of the queer community such as Madonna, Kylie Minogue, Roisin Murphy and Robyn who ruled the 2000’s and 2010’s with their disco inspired interpretations of pop music.

Disco is a genre that is always ahead of its time, and therefore can never die. As the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights, to end racism and social stratification continues to grow, disco will only continue to persist as a getaway car to a better daydream. Take Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia for example, released at the peak of quarantine. Somehow the pulsating four on the floor beat, the familiar sound of a Rhodes piano and dizzying string arrangements made me forget the state of confusion I was in, even if it was only for thirty seven minutes and thirteen seconds. With disco, just a moment is all it takes to imbue our cloudy skies with vibrant colour; it just takes one spin of Diana Ross’ ‘I’m Coming Out’ to feel the glory of being a unique individual.