AUTHOR: Aliyah Keshavjee

GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Luca Ht

COPY EDITOR: Janne Boecker

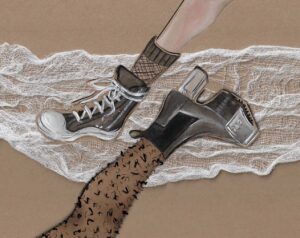

Sometimes, I find myself wondering if our own lives are being spun out of our control by things we’re so used to that they’re imperceivable. As many of us are aware, society has been constructed long before our times, and well-without our input. The systems in place are so deeply planted into the grounds on which we live that it’s becoming harder and harder to differentiate between what’s natural and what’s created, let alone make a decision without the guilt of knowing you’re perpetuating a system that’s working against you–these are the trials of living with the impacts of colonialism and the patriarchy under late-stage capitalism. So much of what we used to have is long gone. Non-processed food, pure and unpolluted nature, a life away from screens, privacy—all things that once were and no longer are. Yet, the loss that strikes me hardest is the loss of craftsmanship in design.

Finding intricacies, keen attention to detail, and authenticity in design seem like finding a needle in a haystack in this age of mass production and hyper efficiency. All over the world, systems of colonialism and capitalism have led us to lose touch with traditional and intricate practices of design, specifically garment design. The art of sustainable and handmade production is fading faster and faster—about as fast as Shein can produce and release a new clothing item (hint: anywhere between 2,000 and 10,000 new individual styles are listed on the site per day). We now live in an era of mass production where the classic twenty year trend cycle is nowhere to be found, and we are constantly being fed with more information than we know what to do with at speeds we are unable to process. What would slowing down fashion in this era even mean?

The current trend in the fashion world is trend—instantaneous selection and purchase, efficient and lightning fast mass production, plus rapidly changing trends and fads constantly informing what we’re inclined to buy. Everything is moving, everything is instant, and everyone is being influenced by the same people and things. How can we ever make fashion slow again? It’s hard not to be defeated when thinking about it, especially when considering that the kind of movement we want and need—one based in ethical, sustainable, and slow fashion practices—is incredibly difficult to sustain in the current state of society. It feels almost as if it is no match for the world we live in today, but fear not. I and many others think it can make a slow but sure comeback.

Fashion used to be slow, and it can be slow again. While slow fashion can be viewed as a protest against late stage capitalism and the long term ramifications of colonization, it is by no means a new concept. In fact, it used to be our default. Before clothing design was as heavily commodified as it is now, handmade and intricate designs were not only the norm, but were fully appreciated for their detail and craftsmanship. Their value was not determined by how fast a piece could be made, how much or little the creator was paid, or how quickly the timeline of planned obsolescence took hold. In cultures all over the world, handmade, handsewn, and hand-embroidered garments held the stories of both the wearer and the designer. Hours of work, dedication, and attention to detail were poured into a piece with love and care, and not everything was made with the intention of profit either. Consider Kantha, India’s oldest practice of embroidery. Kantha is an artform in which women would repurpose and upcycle old garments and embroider them by hand, placing them together in patchwork designs to create something new. This artform was mainly an outlet for creative expression, and brought the creator pleasure and catharsis. These pieces were their journals. They held their stories, their love, and their lives all within their designs. It was never rushed or meant to be sold for profit, so much so that these pieces were often never finished. They were instead continued from mother to daughter, from generation to generation, their stories never ending. Kantha is a great example of the core values so many cultures around the world lost to capitalism and colonialism.

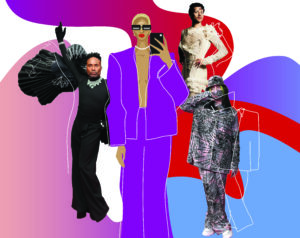

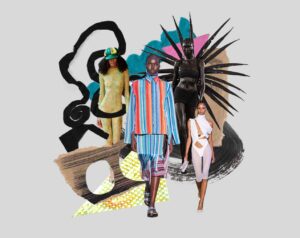

At its heart, fashion is still a beautiful outlet for self-expression, storytelling, and love. Though it may be buried by never-ending trend cycles and 92 million tonnes of textile waste, these core values of fashion are still there. As a fashion student, I am constantly surrounded by the talents of my peers. Everywhere I go, I am met with creativity, intelligence, dedication, and excitement. When I view the works of my classmates, I see self-expression. I see a focus on what their designs mean rather than how much money it will make them. Seeing their work fills me with hope, for if we continue to encourage a critique of current systems and values within the fashion industry, and move towards practices more in tune with historical values in lieu of prioritizing profit, slow fashion can truly survive. Slow fashion doesn’t thrive off of only sustainable and ethical processes. It needs creativity, attention, love, and passion to survive—all the same things that allowed for generations upon generations of the world’s finest works of art and design to be created, and all things I see in my classmates every day. I don’t believe slow fashion is a lost cause at all. I think maybe it’s just beginning, and it’s starting with us.