GRAPHIC DESIGN Zoe Statiris

Rewriting history and recontextualizing the past is often a touchy subject. Misinformation and the defending of long-established social hierarchies throughout modern history offer challenges to those seeking to right the wrongs of the past century. We must now offer people new understandings of how we got where we are today, and what that means for where we are headed.

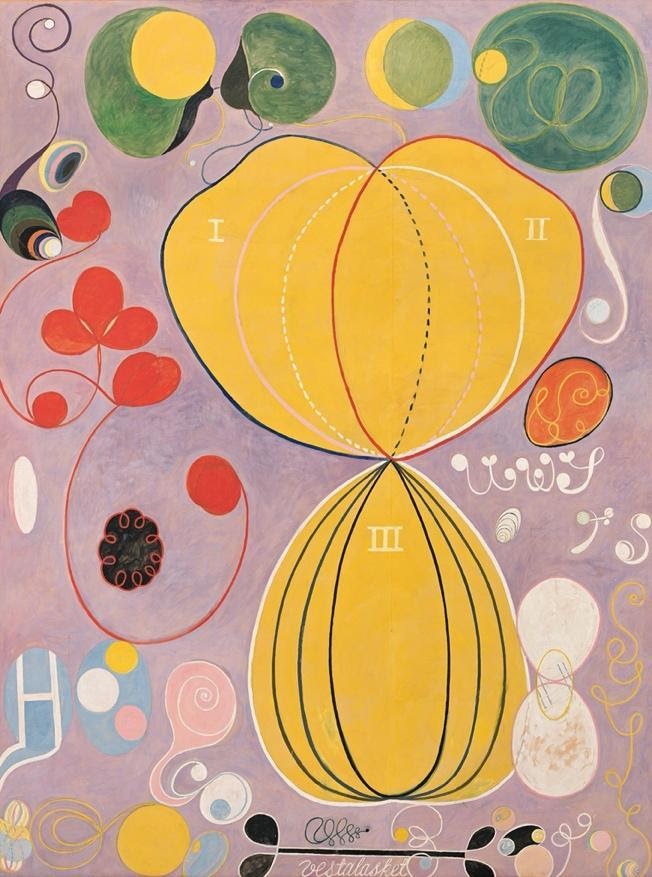

In the case of recently discovered Swedish artist Hilma Af Klint (1862-1944), rewriting history and recontextualizing a century of modern art is an absolute necessity.

Virtually unknown aside from her naturalist work until her first exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum in 1986 (a whole 42 years after her death), Af Klint’s recent distinction as the first western abstractionist has shaken up long established distinctions held by the likes of Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. Her highly celebrated six-month long exhibition at the Guggenheim in 2018, “Paintings for the Future”, showcased her abstract work which was created at least as early as 1906, a whole 4 years before Kandinsky would even synthesize the idea of fully abstract art, let alone create his first non-representational work in 1911. Even Picasso’s infamous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon painted in 1907, considered by many historians to be one of the most important developments in modern art, is predated by Af Klint’s earliest abstract pieces. Af Klint precedes even the surrealists, developing automatic drawing and writing evident in her 26,000 pages of notes found alongside her work when it was uncovered in the 1960’s; in the male dominated modern art history, the fact that a woman actually did it first is cause for celebration.

Of course, abstraction predates Hilma Af Klint in many non-western societies. The distinction of when a work is simply abstracted versus when a work is fully abstraction is also a topic of debate. Like the invention of the camera (which was synthesized by three people around the same time), the argument for who ‘invented’ abstraction is in itself an abstract concept; there is no single “inventor”. Only those who happened to market themselves and resonate with the public best. However, given the barriers that plague artists, as well as women and minority artists especially, it seems fitting to celebrate Af Klint’s radical style as the first in the western discipline.

Some contemporary perspectives in the art world say that Af Klint is partly to blame; she refused to show her work during her lifetime, insisting it not be shown for 20 years after her death. Some historians approach the subject as if there were no external barriers which would have stopped her from showcasing her work as a woman in the early 20th century; it seems only fitting however, given that the art market is notorious for commercializing the once radical. Viewing Af Klint’s work helps us rethink the path of what we call modern art and helps us reconsider minorities and the disenfranchised.

Her focus on spirituality – essential to the synthesis of her work – would not have played out in an era dominated by science and individualism, when people’s faith and trust in religion was waning. The fact that she was a woman probably wouldn’t have helped her case either in this time period, as even Kandinsky was shamed for his spiritually driven abstract manifesto.

After the death of her sister, Af Klint dove into spirituality, focusing heavily on theosophy. Along with a group of women, known as “The Five”, Af Klint conducted séances to try and communicate with the spiritual world; it was then when Af Klint was ‘commissioned’ by a spirit to create her “Paintings of the Temple” series. From 1906 – 1915, Klint would produce almost 200 paintings, totaling 1,300 abstract works in her lifetime. The concern with the spiritual would ultimately lead her to withhold showing her paintings, showing them only to a handful of people. Her plan for their eventual exhibition consisted of a spiral tower (Similar to the Guggenheim), designed so that viewers walk up the spiral to Klint’s ‘altarpieces’, a three-part apex to her series.

The recent discovery of Af Klint’s work is a breath of fresh air in the history of modernism, which has been plagued by my male egotism and toxic individualism.

The recent discovery of Af Klint’s work is a breath of fresh air in the history of modernism, which has been plagued by my male egotism and toxic individualism. Af Klint’s work, although deserving of so much more, Came to us during a cultural moment better suited to view her contributions to modernism. When viewing her work now, it is free of any associations, any historical baggage, we see them how Af Klint would want us to see them.

The MoMA’s 2012 exhibition “Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925” nonetheless left Af Klint’s work out, citing that it was a spiritual exploration as opposed to an artistic one, but just because they weren’t immediately shown doesn’t make them any less influential to art. Art history isn’t about just the past; it is about how we think of the past and our relationship to it. Her distinct and radical style hinders stereotypes about femininity and modesty and pushes them out the window without completely abandoning them in her distinct pastel palette and soft forms.

We also must remember that just because Hilma Af Klint is now being recognized does not mean that all artists are on equal footing. If anything, the discovery of her work amplifies the unfairness that plagues the art world even in today. Hilma Af Klint should not just be written into modernism, her story should be reflected in public discourse when considering the disenfranchised and minority groups that exist in art today.

Modern art historians used to ask why there was a lack of female artists in the era, it turns out there were, the art world just refused to listen.

Af Klint believed society wasn’t ready to view her paintings – something I think she might have been right about. She believed the world would need 20 years after her death to be ready for her work; in reality we ended up needing over 100. Modern art historians used to ask why there was a lack of female artists in the era, it turns out there were, the art world just refused to listen. Rewriting history may seem like a daunting task, but the whole point of historians is to rewrite history. You can’t properly understand the past until you put it into context. After 100 years, it is finally time to put Hilma Af Klint into that context, where she rightly belongs.

As the world begins to wake up, and the marginalized have a much deserved voice, we will see whether more artists like Hilma Af Klint end up coming out of the woodwork.