PHOTOGRAPHY Meagan Dickie

WORDS Katarina Vidojevic

CURATORS Kryselle Cabral, Victoria Hopgood

CW: Contains language pertaining to Sexual Assault and Violence

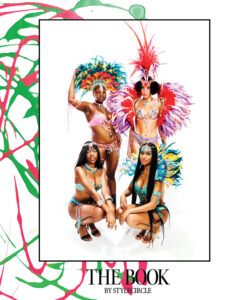

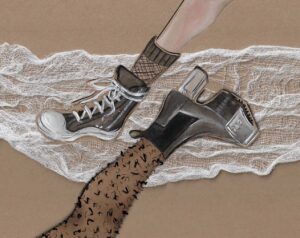

“I Never Asked for It” was curated by Ryerson students Victoria Hopgood and Kryselle Cabral in collaboration with the Office of Sexual Violence Support and Education, and was displayed at the George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre, the Student Learning Centre, as well as the Ted Rogers School of Management building on Ryerson Campus. The exhibit was created as part of a global movement stemming from Bengaluru India where women were sexually assaulted and blamed for wearing “provocative” clothing. The women then flipped the narrative by displaying said clothing to help survivors feel empowered and end the myth that what one wears is a precursor to getting sexually assaulted.

The university environment is a good place to have these conversations: a safe environment where women learn to express themselves–whether it be through what they wear, what they experience, or through academics. It is also a place to learn to converse about important topics such as rape culture, thus fostering an open, progressive dialogue, and educating students of all gender identities that victims should never place blame upon themselves.

ASIDE

RIGHT Age: 23, Location: Toronto

LEFT Age: 18, Incident: Molested by Uncle

From a young age, women have witnessed or been told to cover themselves up: we saw it happen in school, where girls as young as 12 years old are sent to the office for wearing shorts, we saw it in films, in stories, and unfortunately, some women saw it when they experienced it themselves. Having these conversations in university enables women to stop blaming themselves or each other, and helps survivors feel less alone and responsible. It is important to help vulnerable people in university when not everyone has access to their familial support system; seeing these clothes displayed is a powerful way to help survivors know they are not alone.

Every woman knows the fear that runs through them as we put something on that shows a little bit of skin or accentuates the body, yet there is a part of society that even today, shames women for being proud of or showing off our bodies. Society loves to sexualize women, yet when we want to show our bodies off that they worked hard to love, the societal belief is that we are ready to have sex with anyone. The fact is, women are faced with sexual violence no matter what they wear. As seen in the exhibition, it becomes evident that women are not safe from being raped no matter what their clothing is. The toxic and false belief that what one wears can lead to women being susceptible to rape is enabling rapists and blaming us for something that is not a woman’s decision, or fault. When a woman gets raped, she is unlikely to report it. It is a well-known fact, after all, that rapists are seldom prosecuted, and even if they are, they usually get off light, especially if they are privileged. If a woman does choose to report it, she takes a rape kit at the hospital, and gets in touch with detectives: she is then usually asked about what she wore. The whole process is horrific in itself, but the fact that questions about the victim’s choices of clothing are even asked is systemic misogyny.

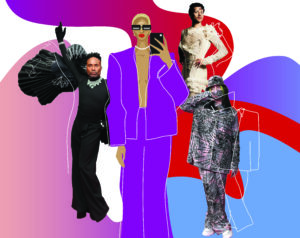

With popular culture moving towards a more progressive stance, the conversation has been in society for the last few years.

With popular culture moving towards a more progressive stance, the conversation has been in society for the last few years. Movements from the film and fashion industry such as “Me Too” have started to enable women to call out sexual predators, and the predators are beginning to face repercussions. Books such as The Handmaid’s Tale have become important sources in education and culture, after demand from the changing politics of the last few years. With these shifts, it feels as though everything is changing for the better. Yet all over the world, women are still living with the fear that what they wear may cause them to get raped. Young girls are still being told to change in school, and rape victims are still being asked what they wore the night they were sexually assaulted. Yes, the conversation exists, however, the deep-rooted misogyny in the question of what one wears when sexually assaulted is still being seen all over the world.

ABOVE Age: 14, Location: Whitby

Seeing these clothes displayed is a powerful way to help survivors know they are not alone, and let women know they are never to blame.

In the fashion industry, this notion of discussion is barely addressed–models that wear clothing on the runway, such as lingerie, are not looked at as objects to have non-consensual sex with- until they come off the runway. Victoria’s Secret models, for example, are seen as mannequins on the runway, yet become playthings when they step into the streets. A recent article titled ‘Angels in Hell’: The Culture of Misogyny Inside Victoria’s Secret written by The New York Times detailed sexual abuse the models faced by casting director Ed Razek. This sexual harassment took place backstage at their annual fashion show, during photoshoots, or trips. It seems as though the runway becomes a safe haven for these models. Rapists can indeed control their urges: they can wait for the models to walk off stage because they know they will be apprehended if they didn’t. The fact that they can wait proves the models’ lingerie isn’t something men can’t resist, but rather an excuse they can use to ensure the fault lies on women.

Society is beginning to speak more about the myth of sexual violence, yet it is still not enough. Victims continue to be asked about their clothing, and perpetrators are getting off with little responsibility and ownership. The world of art and real-life are in stark contrast, with models being able to wear anything without fear on a runway, yet in the real world, a woman must think about what she wears. The exhibition “I Never Asked for It” challenges the notion that the clothing of a sexual assault victim matters. There is never a reason for victims to feel any blame or responsibility, and we must keep making it known and understood that they never asked for it.

RIGHT Age: 17, Incident: Body Shaming by Family