GRAPHIC DESIGN Cindy Phung

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement’s resurgence into public consciousness and media, I’ve been doing some reflecting on the small ways that White supremacy has impacted me throughout my life. I feel that it’s important to take a look inward, in an attempt to correct certain unhealthy thoughts and behaviours that may have been small enough to initially be overlooked, but have been ingrained in our minds from a very young age.

Colourism in itself exists as a result of White oppression; it was and remains to be a way of assigning value to Black people based on appearances.

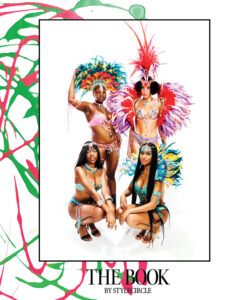

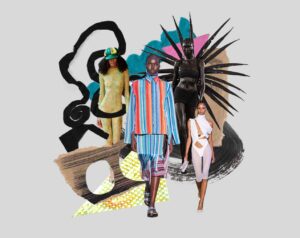

One of the biggest issues that came to mind was colourism. Admittedly, as a lighter skinned Black individual, I acknowledge that I benefit from “light skin privilege”, which is perpetuated by colourism. Colourism in itself exists as a result of White oppression; it was and remains to be a way of assigning value to Black people based on appearances. In this way, colourism is a source of division among Black people. It’s evident that colourism is almost constantly at play when we take a look at the fact that the vast majority of opportunities in fashion and entertainment industries are given to people of colour that reap the benefits of a lighter skin tone. In recent years, brands have taken steps to be more inclusive; however diversity cannot be achieved without equal opportunity for all, regardless of shade.

In many ways, colourism inherently benefits me; however in reflecting on this issue, it’s evident that White beauty standards negatively impacted my self image into young adulthood. Only recently have I come to terms with how detrimental it had been for me, particularly as I navigated my adolescence and came to understand my identity as a mixed person, with one black parent and one white parent.

I clearly remember being told that I’m “pretty for a Black girl”, and although I didn’t take it as a compliment even then, I can now see that statement as blatant colourism, and quite frankly degrading towards Black people as a whole.

Growing up as a young biracial person of colour in a dominantly White area, my older sister and I both struggled with the feeling of being othered, regardless of how welcomed we were in any situation. I feel that this contributed to our need to be perceived as “Whiter” in an attempt to be accepted as beautiful, like our White counterparts. I found myself wishing my hair wasn’t so “crazy”, or “fluffy” as so many people pointed out, and pulled my curly hair into a perpetual bun to avoid dealing with self consciousness, as I could not wear it down without receiving unwanted attention. I figure this feeling was also exacerbated by our Black features, which already garnered attention as being “exotic” and “unique”; although in our schools we were minorities, we were spoken to like we weren’t Black at all. I clearly remember being told that I’m “pretty for a Black girl”, and although I didn’t take it as a compliment even then, I can now see that statement as blatant colourism, and quite frankly degrading towards Black people as a whole. To tell a light-skinned woman that she is pretty for a Black girl, it is implied that dark skin and Black features are not desirable. I look back at moments like this in anger; I feel guilty for not taking the opportunity to stand up for Black women who have experienced racism in more blatant and destructive ways than myself.

When I started to mature, and with the help of Instagram, I began to notice more people that looked like me, who were achieving success in the modelling industry, or simply had thousands of followers praising them. It felt great to see people that looked like me excelling; it served as inspiration for me to a certain extent. However, I found myself feeling slightly put off or jealous of other mixed people that I found to be Whiter looking than myself, with looser curls or lighter eyes and features that were more eurocentric than mine, as if these nameless people were inherently better looking than me because of these things. As I never sat down and thought about why I was feeling this way, I chalked it up to insecurity and just moved on. Looking back at it now, I can totally see that the attitude I had taken was just an exemplification of the ways I had internalized colourism, and unknowingly applied it to my own personal standard of how I thought I should look as a biracial person. I wish I had known that when I would fixate on my sister’s nose when we were younger and convince myself that it was superior because it’s smaller and pointier than mine.

I found this discovery to be incredibly disturbing and therefore difficult to admit to myself. Nobody wants to uncover the significance of their own harmful behaviours, regardless of how much time has passed. However, I believe it’s important to do so because at the end of the day, internalized colourism just contributes to the idea that Whiteness is the epitome of beauty, and clearly that is not the case. Since moving to Toronto and being surrounded by genuine diversity, it has been easier for me to understand that it’s unnecessary to indulge in such unhealthy comparisons. Not only did this way of thinking damage my self image for years, it also fed into the larger system of colourism whether I realized it or not. From examining the ways internalized colourism was a detriment to my own personal growth, I can finally accept myself and others as uniquely beautiful.